End Interview: Social Science Meets Biology

It has been a year since Professor Svenn-Erik Mamelund and his team embarked on their CAS project on Indigenous people and severe influenza outcomes. We sat down with him to discuss the progress made and what the future holds.

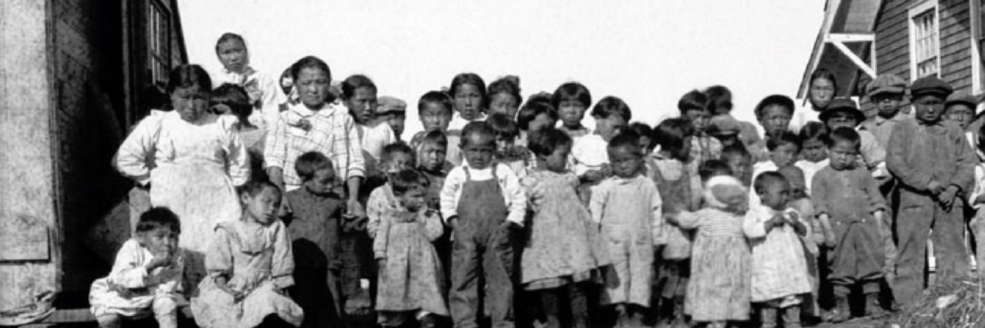

Over the past year, the Centre for Advanced Study has had the pleasure of hosting professor Svenn-Erik Mamelund and his team of researchers behind the Social Science Meets Biology: Indigenous People and Severe Influenza Outcomes project. This interdisciplinary research project has sought to explore the complex factors that contribute to the severe influenza outcomes often experienced by Indigenous communities in Northern Europe, North America and Oceania.

As the project comes to an end, we caught up with Professor Mamelund to discuss his reflections on the project, its findings, and the future of pandemic research.

Through your interdisciplinary project, you have explored the complex factors contributing to severe influenza outbreaks among Indigenous communities across three continents. Could you share some of the key findings that your team has discovered and how these findings have enhanced our understanding of disease outbreaks in these communities?

— We have published 3 papers so far and have several papers in the pipeline. Our first paper found major gaps in reporting data on COVID-19 disease outcomes for Indigenous populations. We found that many countries do not have publicly available data with socio-demographic profiles (e.g., age), leading to a dearth of studies that have empirically examined COVID-19 in Indigenous populations vs. non-Indigenous populations. We concluded that there is a dire need to conduct studies that evaluate COVID-19 outcomes among Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations.

In our second study, we therefore studied COVID-19 disease outcomes in Mexico. This country is particularly interesting as it is a developing country with a large Indigenous population and one of the highest number of native languages spoken. We found that Indigenous groups in Mexico had a 68 % higher COVID-19 mortality rate than non-Indigenous groups and that some of the mortality differences are due to longer care-seeking delays and potentially a lower uptake of both non-pharmaceutical interventions and vaccines.

In our third published study, we analyzed excess mortality during the 1918-20 influenza pandemic in two remote communities in Finnmark, Norway. We found that all age-groups had excess mortality, not only the young adults as has been observed in most non-isolated and non-Indigenous populations globally. Excess mortality in all age groups, including the elderly, hints to geographic isolation, less prior exposure to influenza viruses in the past, and thus less pre-existing immunity as key to explaining the different age pattern of mortality. These factors may also be among the reasons for higher overall Indigenous mortality.

You have specifically focused on understanding both the social and biological factors influencing influenza outbreaks among Indigenous populations. Could you elaborate on how the interplay between these factors has been uncovered in your research and what role they play in the occurrence of severe influenza outbreaks?

— The spread of contagious pathogens requires contact between susceptible and infectious individuals and the right conditions related to transmissibility of the pathogen. The contact process is most heavily influenced by social factors; the transmission process is directly affected by biological factors such as susceptibility or infectiousness, but is also indirectly influenced by social factors. Our goal has been to look at both these processes, with emphasis on the social side of pandemics, such as the impact of ethnicity, cultural practices, age, sex, or social status on patterns of disease spread. Many of these factors are also influenced by biology. For example, the types of food people eat influences their underlying health, which can make them more susceptible to infection itself and the consequences of infection. Social factors such as the availability of adequate health care resources can have strong impacts on the ability of people to survive and thrive following infections.

Multi-disciplinary approaches taking both biological and social factors into account have underlain most of our efforts this year. These are very complex questions, however, so our research has mostly helped to bring these kinds of questions to the forefront of discussions about the impact of pandemics rather than producing easily communicated and specific results.

Based on your research, what are the implications of your findings for future pandemic research and the understanding of health challenges among Indigenous communities? Have you identified any specific measures or strategies that could help mitigate severe influenza outbreaks and improve health outcomes for these communities?

— Our research has highlighted the need for more research on social and ethnic risk groups in addition to medical risk groups in pandemic research and pandemic preparedness. To reduce the pandemic burden, Indigenous communities should be prioritized for scarce vaccines but equally important is to reduce social and ethnic inequalities in exposure, susceptibility, and access to care in interpandemic periods.

In what ways has your CAS stay contributed to the success of your research project? Can you give us some specific examples of how the interdisciplinary and collaborative environment at CAS has helped you advance your research?

— The research we have published, and the ongoing collaborations would not have seen the light of day without CAS. The time spent together over an extended period – in a fantastic building with totally renovated offices and super onboarding staff – has been fundamental for our achievements. We have been able to complete several publications, all of us have made numerous new connections and collaborations, and we have been able to provide substantial opportunities for the training of early-stage researchers. One research assistant found the topic for his master’s thesis working with us, several masters students and PhD students have found inspirations that have been incorporated into their theses, and one fellow claims that being part of our CAS project helped her to get a permanent University faculty position.

What have been the biggest challenges you've faced during this project, and how did you overcome them?

— There have been two challenges. One has been to secure Indigenous representation in our team and Indigenous views in the science and science for policy that we have done. We hopefully overcame some of these issues by inviting both Indigenous and non-Indigenous senior researchers to our advisory board. Further, we sponsored a visiting program for scholars, who spent a couple of weeks with us in the Spring of 2023. Two of the scholars we selected were Indigenous and the third has worked in Indigenous health for many years. We also arranged a pre-workshop for Indigenous scholars before a conference that we organized on Indigenous Peoples & Pandemics (15-16 May 2023). We offered scholarships to five Indigenous participants to enable them to attend the pre-workshop and conference. The conference had representation from all continents and from various Indigenous and non-Indigenous groups. It served the standard scientific purposes but was also a way for us to hold meaningful discussions directly with Indigenous researchers and communities globally. Furthermore, it enabled Indigenous researchers to communicate with other Indigenous researchers from throughout the world.

Another challenge has been to make CAS the promised meeting place between social science and biology. Our experience is that it is hard to find scientists coming from the hard sciences that are committed to doing joint work with social scientists. Luckily, we have had visitors doing lab-work (immunologist/virologists) on influenza from both the USA and Australia, and we are currently working on a joint proposal to combine historical epidemiology and laboratory science to study long-term health consequences after the 1918-20 influenza or so-called 'long-flu'.

As the project approaches its conclusion, what are your plans for carrying forward or building upon the findings and insights you have obtained? Do you envision opportunities for further research or practical implementations based on the results of this project?

— We intend to gather our core group of fellows in Auckland, New Zealand, in the first half of January 2024. We will have a work-week long reunion and a writing retreat to 1) finalize additional planned publications, and 2) keep the avenues open for building future research proposals, scholarship, networks, friendship, and science. The choice of holding the writing retreat in Oceania is not random. Our three main study areas and the home regions of fellows were Scandinavia, North America, and Oceania. This time, our partners from Australia and New Zealand will have less of a travel burden than when they came to Oslo for the 2022/2023 program.